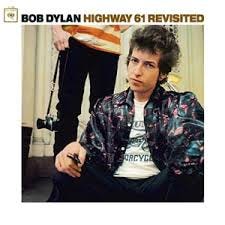

I often say that everything I know about poetry I learned from my mom’s record collection. I remember vividly when, as a 14-year-old, just by chance, I put on my mom’s old copy of Highway 61 Revisited: the electricity of the surreal lyrics, the relentlessly inventive flow of words, surged through me. It seems like a switch was turned inside my brain, and after that all I wanted to do was write poetry.

I would sing the songs in my room until my dad shouted at me to be quiet; I loved the way the words moved in my mouth: that incredible overflow of language garbling around in my body. Maybe more importantly, I analyzed all the different poetic effects and would fill notebooks full of my own versions of lines like:

“They’re trying to endorse/the reincarnation of Paul Revere’s horse”

“God said to Abrham, Kill me a son”

“When you’re lost in the rain in Juarez and it’s easter time too” (this use of and and too!)

“They’re selling postcards of the hanging”

“Here’s your throat back thanks for the loan”

“Electricity howls in the bones of her face”

“Twenty pounds of headlines stapled to his chest”

“Statues made of matchsticks crumble into one another”

I could go on. So many lines from the mid-60s records became my exercise book. Often I would stay up late at night with my headphones on, working and reworking the syntax and the images, the verbal flow. No doubt it was from Dylan that I got my own proclivity of using apostrophe: the love song, the kiss-off song, the tension between intimacy and publicity, presence and absence.

*

This past spring, I went to see the now 84 year-old Dylan play the Morris Theater downtown. The performance was electric perhaps in a different way than the record I listened to thirty years ago (when it was already more than twenty years old), but electric all the same, as the artist reinvented his songs for a different voice, a different age. His voice seemed more expressive, more capable of exploring a strange tenderness in his songs, as he revised his songs.

I have seen him many times over the years, going back to the late 80s, but this time I went with my two teenage daughters, Majken and Sinéad. They had never been interested in Dylan but this past winter we saw the Timothée Chalamet bio pic A Complete Unknown and they were instantly smitten by this myth of youth, identity and art.

The movie tells the story of how the young Dylan arrives in New York City, shedding his old name and identity (as Robert Zimmerman from a middle-class Jewish family in Hibbing, Minnesota) and taking on the persona, ethos and aesthetics of the downtown folk music scene. At the beginning of the movie he stops by to visit Woody Guthrie in his New Jersey hospital, hoping to “catch a spark.”

And catch a spark he does, churning out era-defining songs that start out responding to a folk tradition, then moves on to responding to the contemporary political climate, before moving in a surreal and oracular direction as he sells out and “goes electric” at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965, outraging the same people who had nourished and supported him.

The “spark” he derives from Guthrie becomes an electrical riot. Art it appears works like electricity: It moves in currents, moves through people. If we believe Mary Shelley, it can of course also animate corpses. If we believe David Lynch, it’s a sign that the demons are present. And, as I suggested in a post couple of weeks ago, perhaps art is demonic.

The Demonic Influence of Style: Kenneth Anger and David Lynch

The other day I was in the Walker Art Center gift shop when I heard the familiar “Blue Velvet” wafting out from the movie theater. Since I’d been thinking a lot about Lynch since his passing I went in, expecting Lynch’s noir masterpiece. Instead I found Kenneth Anger’s “Scorpio Rising.” I had never actually taken note that “Blue Velvet” is part of Anger…

*

The movie is a story about identity and growing up, but most of all it’s a myth about Art: How the Robert Zimmerman becomes Bob Dylan in a total dedication to art, how in this dedication his name and biography is erased or transformed by the art, becomes one with the art as the young Mr Zimmerman seems to become a character from a folk song or a tall tale, or multiple characters from folks songs; how he has to reject the very people in the folk music community who at first supported him in order to become the artist he envisioned for himself.

It’s an individualistic myth, but it's also one about the importance of prioritizing one’s artistic vision over all other considerations. It’s a myth told by other modernist artists, including Blaise Cendrars (original name: Freddy Sauser), who in his epic railroad poem “Prose of the Trans-Siberian” writes, “I was such a hot and crazy teenager… And I was already such a bad poet / That I didn’t know how to take it all the way.” It being Art. Youth being both the time of learning and a time of not yet having arrived.

*

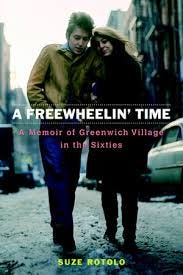

However, there are other instructive myths tucked into the larger myth of Dylan’s early career. If one reads his early New York partner Suze Rotolo’s memoir, The Freewheelin’ Time: A Memoir of Greenwich Village in the Sixties, one finds that she was not the innocent young woman of the movie, but a child of Italian immigrants who had been blacklisted for their communist activities, and who had had to struggle throughout her life while maintaining very practical leftwing politics. We find that she put Dylan in touch with the civil rights politics and avant-garde art that had such a large influence on his life and art. And we find that the downtown folk scene was far more heterogenous than the movie might have us believe, including standup comedians, European writers, avant-garde artists. It was a scene that did not just restrict but also nourished Dylan’s artistic changes.

While the first myth – that of individualistic dedication to art – is important to an artist, these other stories are also essential. Thinking of the artist as an isolated genius is useful in promoting dedication to one’s art, but thinking more socially of creating a social network with people who will challenge and support us is also essential. Perhaps if Suze Rotolo doesn’t take Dylan to see the special concert of Brecht-Weill songs he would never have written carnivalesque songs like “Ballad of a Thin Man.” Similarly, if Dylan had never been photographed by Andy Warhol in his infamous studio, The Factory (or gotten crushed out on Edie Sedgwick), we may never have gotten “Desolation Row” where

at midnight all the agents

And the superhuman crew

Come out and round up everyone

That knows more than they do

Then they bring them to the factory

Where the heart-attack machine

Is strapped across their shoulders

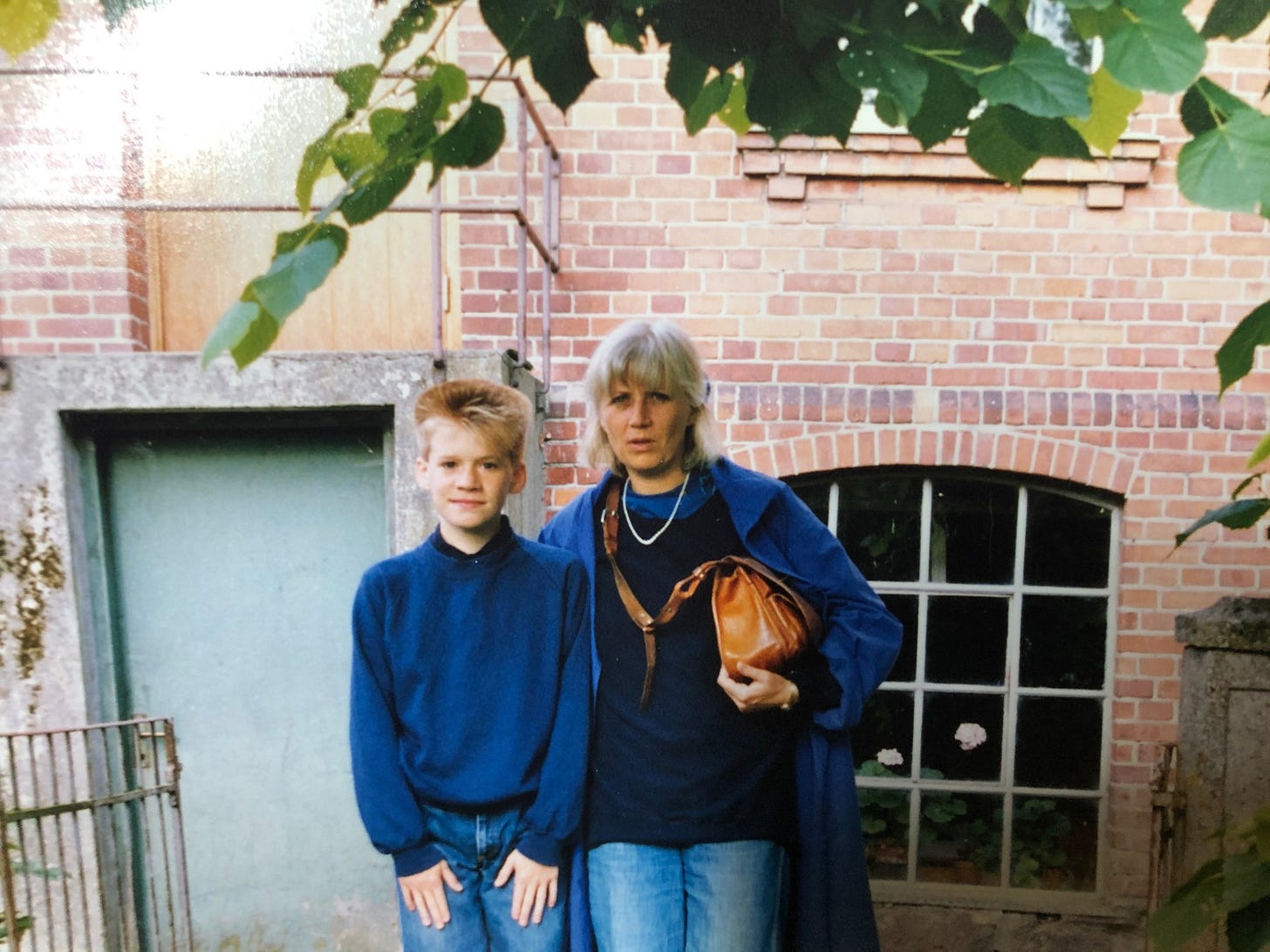

And if Dylan had never written “Desolation Row” or “Ballad of A Thin Man” or “Visions of Johanna,” my mom may never have gone to see him when he played in Copenhagen in 1965, she may not even have named her son Johannes. And I may never have listened to her records as we were moving our belongings as part of emigrating to the US in 1987.

*

J.Hoberman’s new book Everything is Now picks up on Rotolo’s memoir (the book is dedicated to her), exploring in jam-packed chapters all the literary, artistic, cinematic, musical acts, texts and performances of the late fifties through the sixties. Hoberman’s implied thesis is that in this era, in New York, there’s a sense of that “3 degrees of separation” game: except close, anybody at one time – the “now” – are one degree from someone else. The cover of Dylan’s Bringing It All Back Home includes a ton of references including a journal edited by the NYC dadaistic poet Ira Cohen that includes Burroughs, Ginsberg and Jack Smith. The very idea of the record cover as a montage may have something to do with Dylan meeting up with Burroughs shortly before. (For more on Dylan’s connection to visual avant-garde of assemblage see Steven Fredman’s book Contextual Practice).

This is a little while after Dylan hung out with the young avant-garde film maker Barbra Rubin, who is maybe something like a secret hero of this book, due to her movies but also the way she instantly – as a very young woman – seems to weave her way through so many of these scenes and people. Dylan (and Rubin!) also hang out with Warhol and his factory, which created a powerful circuit that seems to drag everyone in – and inspire them! (Even when the inspiration is ambivalent and/or hateful as with Dylan).

Hoberman’s book makes an implicit argument forcefully about art in general, and avant-garde art more specifically: a new-making art that comes out of rampant exploration but also fervent influencings. Art is at its liveliest when people are influencing each other, taking part in each other’s projects, interact in both positive and negative ways. Harry Smith, the ultimate bricoleur and collector of folk songs and maker of occult masterpieces (often lost) becomes a key figure. But Dylan too is an icon of this kind of artistry: constantly taking in new impressions, ideas, textures, to the point that at times he seems to be channeling everything “now” in the 1960s. He becomes an icon of individual greatness, but his was always a greatness of someone able to hypertrophically bring influences into his “own” art. His genius can be read as a form of plagiarism, but this counterfeiting is itself art (ie making faking dollar bills is a kind of art.)

One might say that in difference to the Bloomian vision of the individual genius who has to overcome the influence in order to be their own person, artist, Hoberman’s idea of greatness is an artist who is able to open themselves up to many influences, to be driven by these influences but also to be able to powerfully shape them.

Hoberman’s book also contains a powerful argument about politics: Art, it seems to argue, responds to its time. Sometimes a sound can be the most powerful political statement. Here Jazz music is obviously the most potent case study: Hoberman really calls attention for example to the political ramificaitons of Ornette Coleman’s avant-garde extremism. Dylan’s surreal mid-60-s songs are at least as political as his folk songs. Like the rampant influencings, the politics of the era is carnivalesque, not just in the sense that Carolee Schneeman’s “Meat/Joy” can be read as carnivalesque but that the play – and its maker – operates in a carnivalesque zone of art making.

Finally, I think Hoberman gives an essential insight about avant-garde art: that it functions best when it’s not homogenized; that contrary to the common stereotypes, avant-garde art is engaged with popular culture. Warhol decides to give rock music a try with Velvet Underground around the same time Dylan decides he’s going to “sell out.” But contrary to the common mythic retelling of Dylan “going electric,” the sources of this selling out was already present in the same avant-garde scene that helped generate the folk revival.

*

Lesson: It is a mistake to see “community” as always contemporary, always homogenous, present. It’s a mistake to see it as being at odds with the individual artist, limiting their vision. Art creates influence and inspirations that creates its own socialities – across time and space, through both agreements and disagreements. Art both demands individuality and sociality.

(For my mom, Barbro Göransson, 1945-2025)

(Stångby, 1986, the day we emigrated to the US)