The Treachery of Sound in Translation: Translating Aase Berg's "Loss"

1.

As I noted in my Merwin post, sound has a fascinating, volatile position in how we conceive of and discuss translation. The dominant model of “equivalence” depends on abstracting a meaning from the foreign words, a meaning that acts as “spirit” and maybe even “exchange value” in translation. Abstracting the meaning away from the language allows us to translate the work: we move away from the signifier to the “spirit” which can be “captured”.

But what about sound? If the meaning is the spirit, then sound is - in the Christian paradigm - the body. The place where corruption takes place. In the review I discussed, the critic suggests that Merwin is “seduced” by sound. Sound is sexual, intoxicating. Sound undermines Merwin’s mastery and reduces his translations to kitsch.

There’s always the risk that sound in itself is nonsensical, that it has no meaning. For George Steiner (whose After Babel I quote a lot, it does such a good job getting at the prevailing models of translation), translators are “betrayed, trivially by nonsense, by the discovery that “there is nothing there” to elicit and translate.” He writes that “[n]onsense rhyme, poesie concrete, glossolalia” pose problems for translation because they are “lexically non-communicative or deliberately insignificant.” These modes challenge the idea that the purpose of writing is “signification” – finding the meaning behind the text, the spirit beyond the body – by instead embracing the “insignificant.”

But what if the sound - “the body” - is as important - or more important! - than this abstracted sense? How does one go about translating whose “meaning” is “insignificant” or unsignifying, something that is “nonsensical”? How does the excess of sound push against the idea of “capturing a spirit”, of finding “equivalents”? How might the excess of sound undermine the model of the economic exchange?”

2.

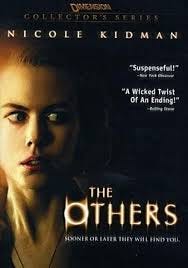

These issues of sound and nonsense, the corruption of the body has fascinated me over the 20+ years I’ve spent translating Swedish poet Aase Berg’s poems. The very title of Berg’s fifth book, Loss, points to the problems of sound and meaning. The word “loss” in Swedish is what you tell a dog when you want it to let go of something. But it’s a bilingual pun: It also is the English word “loss” since the book is to some extent based on a rewriting – or translation! – of the Nicole Kidman vehicle, Others.

The movie is about a mother dealing with ghostly intruders – “others” – trying to inhabit her family’s house. At the end of the movie, she finds out that it is in fact she and her children who are the ghosts, while the ”others” haunting them are in fact the living. Similarly, Berg’s book engages others, the foreign, generating a kind of uncanny theory of translation. Just as Kidman’s character, when I translate Berg’s book I come face to face with language that is uncanny: familiar yet strange. These are poems that reject translation as authoritative, instead vibrating uncannily, sonically between and inside of languages.

3.

Here are a few short poems form Loss in my translation. I’ll talk about them below.

The Swedish language of Loss is distorted, vibrating with English words. The line “rushen fartförtunnlar” contains the word “rushen,” a word derived from the English “rush” – that is, the Swedish “original” is already tainted by an English precedent. The neologism “fartförtunnlar” suggests “fart” (speed) and “tunnlar” (tunnels”). But the phrase also contains the little word “för”– which could mean either “for” (“the rush speeds-for-tunnels”) or a prefix that suggests the activity has been done to an excess – “overtunnels” or “supertunnels.” It’s hard to fit all the ingredients into a line; I have to play with the syntax, with neologisms - and most of all with SOUND - rather than trying to find the correct “equivalent.” The Swedish language of the original cannot be abstracted into “meaning,” “sum” or “spirit.” It “betrays” the idea of equivalence.

I am translating a volatile Swedish, with none of the stability that the term “the original“ usually assumes in translation theory. The line “olycklyckta dörrar” is technically in Swedish, but it’s not standard Swedish, it’s not the kind of Swedish the (illusory) “original reader” could be expected completely make sense of. The word “olycklyckta” is a neologism, but it also sounds like a stutter, a repetition. To begin with, “olycka” means bad luck, ill fortune. Berg joins this standard word with “lyckta.” At first glance, this word suggests the opposite of the first word - “lycka,” or good fortune. With this interpretation in mind, I may translate the neologism as “unluckyluck.” However, there’s a glitch: it does not say exactly “lycka” but “lyckta.” The “t” – that diabolical excess - disrupts my original reading. Instead of a simple “lycka,” we have a mixture of “lycka” (luck) and “lykta” (lantern). Further complicating the phrase, when this neologism is followed by the word, “dörrar” (doors), it’s hard not to hear in “lyckta” the English word “locked.” The English provides a shadow meaning, traversing linguistic boundaries. I translated it as “unlucked doors,” attempting to bring the linguistic movements into play.

These strange phrases betray my understanding of Swedish, my fluency; the language begins to vibrate so that I am uncertain of even more standard terms. Does “omsorg” – a standard word meaning “care” – actually mean “om” (prefix meaning repeated or around) plus “sorg”(sorrow): To doubly grief, to grieve again, to care and grieve endlessly, to grieve around? A restricted reading of the “meaning” of the book would want me to find the correct meaning (“care”), but by this time I am so involved with the sound of the texts and the parts of the words, that I want all these possibilities to vibrate in the translation. There is no stable poem that can be “lost in translation”; the original is already in translation, in transit, vibrating, noisy – a deformation zone in which the binaries like body/spirit or value/money are shown to be illusory. With these strange Swedish contortions, including the presence of English words that seem to infect the Swedish, I read the text almost like a stranger, almost like someone who cannot read it for meaning, but rather to read it for sound, for the distortions and puns - for its “betrayals.”

4.

Traditionally, translation is seen as demanding a hard-earned mastery of languages – both one’s first language and a foreign language. This mastery of the foreign language is construed as a mastery of “signification,” but what happens when sound – and its bodily, physical impact – is allowed primacy? The poem, “Naja” (a slang word, a sound) ends with the one-word line “dön.” There’s a hint of “dö” (die) and “drön” (drone) as well as “ön” (the island, which makes sense because The Others take place on an island in the English Channel). It’s a vibrating word. When I ask Berg about it, she says it “gives the same feeling as ‘dån” [loud noise] ”and that the only time it appears in Swedish is in the compound word “tordön” (an archaic word for “thunder”).

In her work, Berg often uses the ö-sound to suggest a kind of dumbness, a “stuplime” moment, as Sianne Ngai has argued: “Homer’s dull stupor in the wake of unexpected loss produces its own “thick” language—one that initially suggests an inability to respond or speak at all—by eroding formal distinctions between word, sentence, and paragraph.” The way I’m using it, stuplime becomes a sublime asignifying, a drone.

In the end, I feel like what holds the poem together is the sound – especially that ö sound. In my translation, I left the word in Swedish. The sound is a stuplime sound that betrays signification, and thus a traditional model of translation. Instead it forges a sonic intimacy that infects me. That is why I used the word – or really the sound – “dön” in my translation. I’ve translated it by keeping it as a sound.

[Quick note: this ö-sound is key to Berg’s latest book, Aase’s Death, which came out last year in Sweden and next year in my translation from Black Ocean. I write more about the coma-like feeling of the ö-sound in the translator’s note to that book.]

5.

Berg’s poems suggest a game of mimicry, perhaps even a children’s game (perhaps even a game played by ghost children) – full of onomatopoeia and strange neologisms and glitched-up language. It takes me back to Walter Benjamin who, in “The Mimetic Principle,” suggested that indeed children were the last participants in mimicry – especially onomatopoeic language games – in a Western culture that demands the kind of utilitarian goals that Bataille rejects in his writing on “a general economy.” In Bataillean games, the goal is not utilitarian or even conservational. These are games of excess and noise, excitement and exuberance. They are contagious. The only way to translate such poetry is to become infected, seduced.

6.

This child-like onomatopoeia is something Berg herself describes in her beautiful essay “The Language of Madness.” In this article (or maybe manifesto), Berg imagines that language precedes human beings, that it’s a virus hovering around waiting for an animal with sophisticated enough jaw to be able to take the language in its mouth. At first, it’s “paradisical,” a “happy babbling for the sake of babbling.” However, soon it is “instrumentalized,” made into a tool for power and capital. The place it survives, according to Berg (like Benjamin), is in the babbling of children, which is where she draws her inspiration for poetry. Might we as translator not follow Berg’s example and draw our inspiration for paradisical babblings? Instead of worrying about establishing mastery and conserving energies, we might, as in Bataille’s favorite quote from William Blake, find beauty in “exuberance.” Might we instead of constantly worrying about getting everything right, finding “equivalents” and being “faithful” to some illusory original, instead join the non-utilitarian babbling? Might we instead of trying to maintain national boundaries, join the deformation zone of poetry?