I.

I’m teaching the “publishing practicum” class at our MFA program this year, and of course I have to make things complicated so I start out having discussions about what it means to publish, assigning some books and essays by Walter Ong, Marshall McLuhan and their ilk to think about the transformational effects of print technology.

Basically, both McLuhan and Ong (Ong was McLuhan’s student) studied how the transformation from oral/aural culture to print culture - especially print culture standardized by the printing press - changes the way we tell stories, the way we think of writing, the way we make sense of the world. As McLuhan famous put it, the medium is the message.

According to Ong and McLuhan, oral literature (a contradictory phrase) is marked by repetition, the use of cliches/types, as well as a sense of literatures as belonging in a communal context, in an event of the telling. We have this idea of oral performers as having amazing memories, allowing them to perfectly replicate long epics, but Ong found that while these performers claimed to perfectly replicate the epics they recited, they had a very different idea of perfectly replicating, one that allows for quite a bit of what we might call improvisation. The think they are perfectly replicating the original because in oral cultures these terms - perfect, replicate, original, meaning - mean differently.

In contrast with oral cultures, print culture removes the text from that event-ness of performance, standardizes languages and texts, creates an expectation of closure. But it also allows writers to focus on creating more complex characters, to deviate from various patterns and forms. This leads to a model of originality that is such a powerful ideal in our culture.

Applying the model to contemporary poetry discussions, it strikes me that the pervasive idea of “accessible” poetry is the most print-based ideal imaginable. We access the text, go through the visual text because we are in control. Interpreters. Deviations from the rules interfere with the us “accessing” the meaning.

I’m interested in the way oral culture embraces improvisation within the framework of mimicry, while the print culture emphasizes closure and standardization while giving rise to an idealization of originality that necessarily marginalizes translation as “unoriginal” and necessarily flawed (poetry is “lost in translation”).

II.

I’m also interested in now translation fits into this complicated node of differing models of originality and mimicry. Once you’ve read about the effects of print culture, it’s hard not to notice how the position of translation has come to be defined by print culture. With the standardized, closured model of the text, we begin to judge the translation according to an impossible standard of “faithfulness”: We put the original next to the translation and look for deviations. If you look at reviews of translated titles, they usually focus solely on perceived deviations, mistakes. The text is complete, stable, enclosed - so the translations cannot ever be correct.

To deal with this impossibility of translation, we either make the translation “invisible” (in Lawrence Venuti’s terms) to avoid having to think bout the text as a corrupt version and the translators as unoriginal mimics (see my essay on Poetry Foundation that grapples with this dilemma), or we treat the translators almost as authors themselves (highly visible), so as to make them “originals.”

Translation is a scandalous act in our contemporary print culture because translations do not comply with print culture’s model of the text. Translation generates versions of originals, while asking us to read them as if they were originals. My own sentences falls apart: are translations versions or originals? My inability to define just what a translation is indicates its problematic position in our literary culture.

III.

Looking at the changes from orality to print culture might help us thinking about translation not only as a scandal (though I think it is important to dwell in this contradiction) but also more expansively. How might for example the performers of epics in oral culture provide a different model of translation? Or even: how might their practice make for a more volatile and interesting model of originality, one that does not depend on the exclusion of mimicry, and one in which “errors” or “deviations” are not seen as deviations resulting in the “loss” of the original?

IV.

Just listened to this Weird Studies episode on McLuhan that focuses on McLuhan’s prediction/observation that the electronic age is leading to a a new revolution in thinking: we are moving away from the visual culture of the print age toward a culture closer to the oral cultures, or “auditory” cultures.

The results of such a shift is a move from the linearity of print culture moving toward to the event-ness of “acoustic space.” This acoustic event is “multi-sensory” and “synesthetic.” This new age is not merely sonic, it’s multi-media. In this event, it’s much harder to see oneself as an individual separate from others, from the event. Rather than linear time, we get “an animate, pulsating, moving, vibrant interval.” (I’m now quoting the Weird Studies hosts.)

Or as Walter Ong puts it: “We are enveloped by sound. It forms a seamless web around us.” We are immersed in the media, permeated by it. (The ascendency of “the vibe” in contemporary culture must be an indicator of this shift away from print culture.)

V.

I find this vision of the digital age (whether correct or not) holds a lot of potential for translation. Perhaps we can already see some changes in this regard: the translation as a kind of performance or translation as something multi-voiced (as in Douglas Robinson’s writing); multiple translations of a text (rather than always having to find “the authoritative translation); and perhaps most of all a focus on sonics.

I have written about sound and translation in a few of these posts. I wrote one post about a take-down of Merwin as translator that argued that Merwin was “seduced” by “the sound” of the foreign text, leading to a loss of mastery, a loss of correctness. Sound is a scandal in print culture: it leads us away from authoritative “capture” of the signifier, the spirit of the text, instead allowing the body to be brought into the operation, allowing something bodily (a “seduction”!) to enter into the event of translation.

In another post, I wrote about translating Aase Berg’s “Loss,” and how the “ö” sound in “död” was more important to me than the signification of the full words: “These strange phrases betray my understanding of Swedish, my fluency; the language begins to vibrate so that I am uncertain of even more standard terms.”

Perhaps this can be seen as an effect of a post-print age?

As a translator I am drawn to the model of the translation as event, as an act of mimicry that allows for the necessary improvisation without losing the idea that it is an imitation, a re-sounding of another text. But I also don’t want to think of it merely as something I set up side-by-side with “the original” and look for problems, errors or glitches. Here orality and post-print thinking can lead to new and more productive notions of originality - and translation.

I like the idea of translation as a performance in an “acoustic space.”

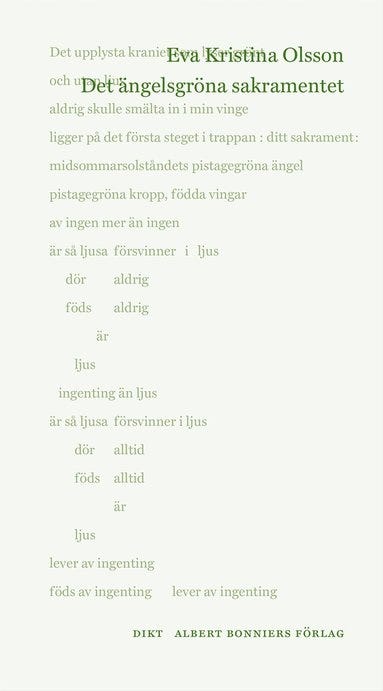

It should come as no surprise that one of the favorite texts I have ever translated is Eva Kristina Olsson’s notoriously event-like angelic encounter The Angelgreen Sacrament.